Episode 14 - The Accidental EIR with Peter Winton

The breath gave me the confidence to say, I think I know what's on the other side of this, so I'm happy to run towards it and give it a go. May come onto this a bit more later, but one of the things that all that taught me was that the most powerful three words in the English language were I don't know. Right? And I think I was the idiot who had the had the courage to actually, when somebody said, what about this? I had the courage to say, I don't know.

Peter Winton:But I could then go off somewhere and find out. And that's one of the joys of working at the university. They're not afraid to say, I don't know, Because within short, they'll come back and say, because of this, this is the answer. This is how it's done.

Ilya Tabakh:Welcome to EIR Live, where we dive into the lives and lessons of entrepreneurs and residents. I'm Ilya Tabak, together with my cohost, Terrance Orr, ready to bring you closer to the heartbeat of the innovation and entrepreneurial spirit. Every episode, we explore the real stories behind the ideas, successes, setbacks, and everything in between. For everyone from aspiring EIRs to seasoned pros, EIR Live is your gateway to the depth of the entrepreneurial journey and bringing innovative insights into the broader world. Check out the full details in the episode description.

Ilya Tabakh:Subscribe to stay updated, and join us as we uncover what it takes to transform visions into ventures. Welcome aboard. Let's grow together. We are here today mostly because Peter got a little curious when a small message popped up in his LinkedIn inbox saying that, Hey, you're an EIR in The UK. I haven't talked to a lot of EIRs in The UK.

Ilya Tabakh:Also, I've been hearing about this Royal Society scheme for EIRs and would like to learn about that. And I'm glad that Peter's curiosity got the better of him. This is probably two and a half years ago. We've had the pleasure of having a few conversations since then, but it's sort of my pleasure. And I'm excited to have Peter on the podcast with us because he's got just like a crazy background and multiple careers worth of experience.

Ilya Tabakh:I'm excited to tap into that. Peter, maybe to get started, we always like to kind of go back to the early days. And so maybe I'll ask you to introduce yourself and talk a little bit about, you know, kind of where your professional life started, and maybe we'll even pull it back beyond that a little bit.

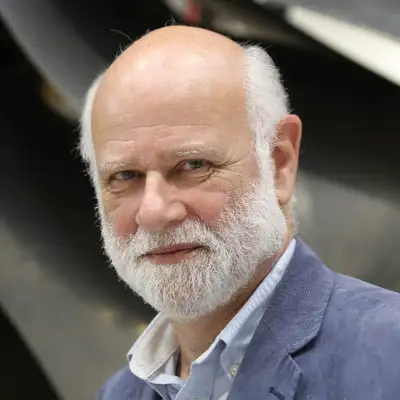

Peter Winton:Sure. Yes. Well, thank you for having me on, guys. This is an experience, so another experience to chalk up. So, yeah, my name is Peter Winton.

Peter Winton:I am basically a mechanical engineer who has spent most of their time in businesses in the manufacturing side of things and laterally in manufacturing technology development. I started in 1971. I did an apprenticeship with Ford Motor Company, and I went on then to become a buyer and I bought large amounts of machinery and equipment. So there's a factory down in Valencia in Spain, which makes or used to make the Ford Fiesta, And I bought loads of kit that went inside there. And then the other interesting buy that I had was process control computers.

Peter Winton:So I bought the first finite element analysis computer that went into Ford in The UK and the first automated drafting machine that they had, which today, I mean, it was about the size of a small bungalow, this thing. It was phenomenal. It could draw the side view of a Ford Granada estate, which was about 20 feet long, full size. I mean, was huge. It was great fun going down and seeing the technology, going into the guys who were using the CAD and they were in their little dark rooms because the screen was just some little faint green lines, nothing like what we have today.

Peter Winton:Was great fun. And a friend of mine who I met when I was a buyer went across to a company called Desousa who were in North London and they were looking for somebody, the old man called a production coordinator. What it turned out to be was let's go and upset all the people in the factory because the factory in Hedgeware was not, well, probably still in the nineteenth, let alone the twentieth century. The problem was they had a lot of ways of making things which were really, they were on top of and they were very, very good at, but they were never going to survive. Manual lays, manual milling machines, things like that.

Peter Winton:But we had a factory down in Anmering on the South Coast in Sussex and they had a lot of automated machinery. What the old man was looking for was somebody who would help him transfer the volume work down onto the automated machine tools and equipment.

Ilya Tabakh:You know, before we dive into that, it's interesting. So a mechanical engineer trained to sort of design, do statics and dynamic load and things like that, and then you're buying stuff, and then you're plugging into how to run a production facility. I just want to pick at that a little bit because that's probably not the role you thought you were training for.

Peter Winton:Yeah. Probably misled you slightly in that my my training was never about designing things or doing equations or, you know, Greek you know, putting Greek letters in the right order. That was never what I did. So that was the start of my self teaching, if you like, Ilya. But yes, sorry, go on with your question, please.

Ilya Tabakh:No, no, that's great. Think that, you know, one of the things that we found with EIRs generally is that even before they started their formal education, they're taking things apart. They're curious. They kind of take leaps. I'm sure there's a little bit of that in your background, but we'll dig into that here in a little bit.

Ilya Tabakh:And then the, you know, sort of formal education, they tend to either do things outside of the formal curriculum, get good at sort of understanding what they don't know, and helping build that up. And so it seems like, you know, you just mentioned kind of your self education. It sounds like you're following maybe a similar pattern. That's kind of my question is kind of from the formal education to your first role, you know, what was that transition like?

Peter Winton:So the formal education was what was called a Higher National Certificate in Production Engineering. But because it was the Ford apprenticeship scheme and I was not a craft apprentice, so I didn't go down and work in the tool rooms and all the other highly skilled areas, It was a technician apprenticeship and therefore you were expected to go out using your technical background to help the company. In cases of buying machine tools and equipment, you had to have some sort of technical knowledge of what you were buying. I mean, you know, just hanging up the blue oval and saying I'm from Ford was great, but then once the order was placed and there was an amendment to the order, then they would try and take you to pieces and you had to know what you were doing. So that was, if you like, was my early formal training.

Peter Winton:Think the ten years I was at Ford, I think what I got out of it was I had a very good mentor, guy named John Barton, and he taught me to think. You know, we downstairs would for lunch and he would pose questions to us young technician apprentices at the table and we had to try and answer them and you had to learn to think. And so that was very useful. As I say, a friend of mine went to a company called Desuta. The old man was looking for somebody.

Peter Winton:I went and joined it. I did reasonably well and I ended up running one of the small divisions that made press tool die sets and plastic mold sets. And that started to teach me about business. That started to teach me about, well, hang on a minute. This isn't all as simple as it looks, is it really?

Peter Winton:You know, it's not just a question of going down on the shop and saying to the guys, we need to make 20 of these. The customer wants them next week. You know, somewhere, where am I gonna get the money from to buy the material? You know, how am I gonna market this stuff? How am I gonna sell it?

Peter Winton:And that was an early teaching and the fact that you can't do it all yourself. You have to build good teams and you have to surround yourself with good people. So I enjoyed that. And that came to an end when the, DeSouter family sold the company. The company didn't want the diamould set division and it was sold to a couple of guys, the Danley brothers.

Peter Winton:And I've got to confess I didn't like working for them. It really wasn't. Nah, it's not for me. This is not the way that I wanted to do things. And so I had my second major lesson, which is if it's not going right, give it up.

Peter Winton:You know, people think it's a failure to give things up, but it was a making of me, you know, and I gave it up. I left. I had a small amount of money that they gave me, due to my contract conditions. And I left. I went basically got bumped around the early recession sorry, the recession of the early nineties.

Peter Winton:And I ended up running a small subcontract company for a guy who was you might have to cut this out, didn't really know the difference between being a shit and being a bastard. Again, it lasted six months or I lasted six months, let's put it that way. But I then ended up at Rolls Royce and that was great. And I started in one of the small subsidiaries they had, a company called Allen Gears. We made power transmission gearboxes, parallel shaft and epicyclics.

Peter Winton:And that taught me a hell of a lot about how you design things, how you take account of forces, how you simple things. I mean, it never occurred to me. Power is torque times revs. Never crossed my mind. And it's a really simple thing that a lot of people don't know.

Peter Winton:But when you look at things, then you can see how that works. From that, I went into doing some lean manufacturing in Rolls Royce, and that was really very interesting because again it started to question all the things I thought I knew about how you schedule things, how you work machinery and equipment, how you assure quality and things like that. It really tested a lot of things I thought I knew, only to discover I didn't really know. But again, that taught me a lot.

Ilya Tabakh:And just to point out before we kind of dive in, I think there's a lot of meat in the Rolls Royce part of your story here. But I love the fact that you had some experiences that you didn't love so much, to say it in a different way. Because I think that, you know, there's a lot of folks that have spent their kind of life in, you know, kind of one career, one field. They sort of haven't had a variety of experiences. And I found that, you know, being and switching and sort of seeing that things could be drastically different and they don't necessarily have to be terrible or great, as in some cases a superpower, because both that you can, you know, the dogma of how it's supposed to be is just that, right?

Ilya Tabakh:And so you kind of get some perspective. And I love that that's in your background. I'm curious how you would react to that, you know, whether, you know, kind of reflecting on that, what that gave you further in your career.

Peter Winton:I would agree with what you're saying completely. I think what it gave me was two things. One was I learned that my career was never going to be about height. And the only alternative to height or, you know, as the saying goes, the only difference between a rut and a grave is the depth. If you don't wanna be in a rut and you and you you've you've that, you know, height's not your thing, then the only dimension left is breadth.

Peter Winton:And so I was very keen to go and do things that I hadn't done before. I had the confidence that I would be able to do them because they were either in areas that understood or they were in areas that interested me. And by the time I got to Rolls Royce, I had certainly concluded that I do my best work in things that I enjoy doing, which doesn't mean I wouldn't take a challenge. I mean, when I retired, my little eulogy my boss gave me was started off with. I never knew Peter to refuse any challenge I gave You know?

Peter Winton:And I think, you know, my answer to that at this distance is I chose my bosses well in that I didn't choose a boss who would, you know, just tell me things that I couldn't do. He was very appreciative of what my skills were, and and so we got on really well. My point being that if you enjoy doing something, you will always do it well. If it's a chore, you won't, and quitting is not a problem. You know, you have to set it in the context of your own position.

Peter Winton:I had family, you know, I couldn't just quit and do nothing. You know, I had family. You know, bread had to come onto the table and all of that sort of thing. But my point is that if you always aim for height, then you must accept that it's an inverted well, it's a triangle, and there's only one person at the top, and there's tens of millions, hundreds of millions lower down. So where where do you wanna live?

Peter Winton:And you can't live somewhere if you feel you're just turning a handle.

Ilya Tabakh:Yeah. The the analogy I love is if if you keep digging, eventually, you're in the bottom of a well, and your perspective, you know, when you look up, you see a very, very small part of the world. And And I actually think this sort of horizontal nature of your career and the fact that you got hands on experience ordering things, seeing how these things work, ultimately really contributes to understanding where to put leverage, right? Think we'll probably dig into that a little bit on how you're able to apply that perspective in the role as an EIR. But I just want to kind of highlight that because if you don't know parts of the terrain from a close view, it's sort of hard to know, Hey, we should really do something over there because it's going to have this downstream impact somewhere else.

Peter Winton:That's right. I think the other thing I would add to that, Ilya, is because I was able to see across, I got involved in a lot of different businesses and a lot of different issues, a lot of different projects. It gave me a really good understanding of where things are used and how things are used and how things work. Right? So, you know, cars that I worked on in Ford in the seventies were literally drawn with a, you know, a ruler and a pencil.

Peter Winton:You know? When a car was finished and it went into production, it it was drawn parts of the bodywork were drawn on plastic film. It's called Mylar. Much much more durable than paper. But when you've got a car with, you know, a 100, a 120 panels on it, and then they go to the die manufacturer who has to make them, in those days, there was nothing.

Peter Winton:He would get a pair of calipers, a manual pair of calipers, he'd measure between two points and he'd say, I think that distance is, you know, 2.4 inches or whatever it was. And you would have to go to the flat two d drawing and work out whether that was correct or not. But the problem with mylar is it's plastic, and over time, as you roll them out and roll them up again, it stretches. So then you get the wrong answers. Right?

Peter Winton:So every one of those had to be etched onto a sheet of aluminium, which was screwed to a wooden table, which was in the middle of the drawing office, and there it stayed for the life of the car. You know? Now today, somebody just picks up his mouse and goes click click between two points on the screen and says that's 1.7648 millimeters. Boom. So it was a very different world and you had to know how these things worked And that's a massive advantage to me anyway.

Terrance Orr:I'm gonna jump in here, Peter, because, it's fascinating. I was letting you and Ilya like spar a little bit, in in the conversation because I'm I'm taking a lot of a lot of notes here and, I'm already starting to see similar sort of things that most EIRs don't recognize as they're going through it before they take their first opportunity as the for this methodical role that they never heard of before in in the ether. And it's a few things that you've mentioned that I just wanna, you know, sort of bring together for our audience. One, you've done a lot of different things. Most of the EIRs that we talked to, they've touched and done a lot of different things throughout their lives and careers.

Terrance Orr:And some of them have gone deep in things and some of them have had the breath like like you in in in your career. So and and what you guys are hearing is the details. Right? You listening to Peter talk, you can tell he's been into the details. He's actually been executing and designing in in the trenches.

Terrance Orr:Right? Because only people who have been in the trenches can go to this level of detail. Right? And I think it's important to be able to share those stories and to know that most EIR's at careers look like quilts. It's not a straight line.

Terrance Orr:You've done a lot of different things, right, along the way. And I think that's super important. But I think more importantly, you know, he never never ran from a challenge. Right? So even if it was hard, even if he didn't know how to do it, he ran towards it.

Terrance Orr:And I think that's a really good kudos from your former boss to saying, I've never known Peter to run away from a challenge. Right? And I think that's a common theme that we see in people who eventually become, you know, entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs in residence is that they raise their hands, they accept the challenge and they run towards the things that they are afraid of. And I think that's important. How would you react to that?

Peter Winton:Yeah, I think I completely agree with you. Think it's, you only need to run towards things if you've got some idea in your head what you're gonna do and what is what is on the the other side of whatever it is you're running towards. You know? It's no good running towards a fire if you don't know there's an exit on the other side of the flames, is it? That's the point.

Peter Winton:And so the breath gave me the confidence to say, I think I know what's on the other side of this. So I'm happy to run towards it and give it a go. We may come onto this more a bit more later, but one of the things that all that taught me was that the most powerful three words in the English language were I don't know. Right? And I think I was the idiot who had the courage to actually, when somebody said, what about this?

Peter Winton:I had the courage to say, don't know. But I could then go off somewhere and find out. And that's one of the joys of working at the university. They're not afraid to say, I don't know. Because within short, they'll come back and say, because of this, this is the answer.

Peter Winton:This is how it's done.

Ilya Tabakh:You may not find this so fascinating, but I spent a little bit of time when I was in university working on my PhD in a fellowship to figure out how to communicate STEM. And so part of that was really thinking about how to teach kids about stuff. It turns out, I'll save you a lot of the work product, but the result was that metacognition essentially a kid's ability to reason about what they know and what they don't know, was one of the better indications of how well they were going to do in kind of an educational setting, whether supervised or unsupervised. And so it's not so surprising, you know, kind of from that experience that a strong I think both saying I don't know, but ultimately, maybe more broadly, having a good capability to understand where are you comfortable, where are you not, and maybe even a little bit of anticipation of where are areas that you're not even aware of that could be an issue, you know, and how would you kind of gain a little bit of grounding and foundation there. So, you know, I've thought I guess it wasn't that surprising of a takeaway, but it was an interesting, you know, top tier indicator that I didn't expect to be such a strong signal.

Ilya Tabakh:So I just wanted to kind of bring that in there. That metacognition thing's pretty strong.

Terrance Orr:And I'm gonna double down on this a little bit, Peter, because you mentioned the word university just now. And I wanna ask you a question about, you know, can you tell us a little bit more, you know, in our sort of prep call, we talked a little bit about your role sort of managing the university technology center, right, at Nottingham while you were at Rolls Royce. And that sort of gave you exposure to sort of like potentially moving in towards that world. Can you tell us a little bit more about that experience and how that potentially led to what you're doing?

Peter Winton:Yeah. So to put it into context of the previous story, I did delete manufacturing a bit, but I worked for a really nice guy and I went to him one day and said, look, I think I've had a bit too much of this and I seem to be the guy who's sitting in the corner here when somebody suggests something saying, No, we've done that. Is there something else I could do? And he gave me a little project to do, which went very well. And I ended up in a part of Rolls Royce called Manufacturing Technology.

Peter Winton:And we were the people who did all the research and development on manufacturing processes. So you have R and D on product, but you also have R and D on the way you make the product. And Rolls Royce in many areas were leaders of that over the previous, well, since the sort of middle eighties, they were leaders in producing product that did things that other people couldn't do. And manufacturing technology was a central team, but we had to influence other businesses both to get them to come to us and say, look, we've got these issues, can we work them out? But also for us to say, we develop these types of processes and can we introduce them into your businesses.

Peter Winton:In order to do that, and this applies equally to the product, companies like Rolls Royce, and we're talking gas turbines Rolls Royce now, we're not talking about motor cars, BMW make them now and we don't talk about that. But the gas turbines, they are the huge engines that you see hanging off the wings of aircraft. Rolls Royce specialize in what's called twin aisle. So in other words, as the name suggests, it's got two aisles that you walk down when you get inside the fuselage. So, you know, your seven four sevens, seven eight sevens, three fifties, and so on.

Peter Winton:And those products are very, very sophisticated. They're complex and their performance requires you to constantly looking at new materials, new methods, new aerodynamics inside the engine and so on. And that requires you to have a very good network of fundamental scientists. Now Rolls Royce's competitors either didn't do it or did it on their own dime. And Rolls Royce wasn't big enough to do it on its own dime.

Peter Winton:So a very clever guy came up with the idea of having what he called university technology centres. And the object of the exercise was that the university and the company got together, the company made contributions annually for the number one purpose of paying for PhD students to study new science in areas that were of interest to the company. So that was a university technology centre. So if you take for example the transmissions UTC which is also at Nottingham and they did work into transmitting power from different parts of the engine to other parts of the engine. So without giving you a boring gas turbine lecture, basically the bit at the back drives the bit at the front and the two bits in the middle drive each other.

Peter Winton:But there's a lot of power to be transmitted. So on takeoff, it's something like 60,000 to 80,000 horsepower coming out of parts of the engine. A lot of power. The second UTC at Nottingham was the manufacturing UTC. And for reasons I won't bore you with, it had dwindled, had withered on the vine.

Peter Winton:And my boss said to me, Peter, would you like to go over there, take a look at it and see if you can repurpose it for something that would help you? And I was one of 32 global specialists and my global specialist in which I was responsible across the whole of Rolls Royce was tooling and fixturing, which is a massive subject which I'm not going to get into. So I went across there. That was 2010, I think. Let me just work that out.

Peter Winton:Was it no. It was earlier than that. 2007, 2008, something like that. I went across there. They had a new, UTC director, and I met him and the UTC consisted of him, a very clever researcher who ended up working for Rolls Royce and one PhD student and that was it.

Peter Winton:And when I asked them what they were working on, the answer was not a lot. So I went round and talked to a number of people including the guy who was responsible for all the UTCs for the company and said, well, how do I do this? What do I do? What can be done? And the upshot of that was, together with Professor Dravos Segazinte, highly motivated guy, really keen to make a success of this, which I'll come back to.

Peter Winton:And he said, well, we ought to be doing this sort of thing. I said, and I'm trying to do this sort of thing. So can we put these two together and come up with a package of work that we could justify our annual contribution on? And he said, yeah, so we did it. And we presented it to my boss and he was very keen on it and very receptive.

Peter Winton:And afterwards when he was talking to me, I just said, look, I think we can make a go of this. If you'd like to give me a couple of years, let's try. And he said, Okay, let's try.

Ilya Tabakh:Before we dive into that, I'm just curious, what was your first impression? And maybe what sort of surprised you about the academic folk what didn't? Because it's like that's the the the meeting between industrial and academic worlds. And I have a lot of background on this in The US, I I'll add some color commentary later. But I'm always I'm always fascinated by first contact.

Ilya Tabakh:Right? Like, when you actually go from the Royals Royce contacts to the academic, I'm just curious what your experience was like.

Peter Winton:I think initially, I just wondered what they were supposed to be doing. I wondered how they did it. But because it was so I mean, in a way, it was so closely allied to what we were doing in ManTech that I didn't wonder much more than that. But it was only as time went by I think the best way I can sum this up is as time went by, I began to realize this. In Rolls Royce, our principal competitor in gas turbines was General Electric.

Peter Winton:So everything we did, we looked at General Electric. What was the impact on General Electric? Were we getting orders? You know, all you know, was our technology better? Was our engines better?

Peter Winton:All of that sort of thing. And in business, in industry, competitor is somebody else who's doing something that you're doing. Right? What I came to realize was in academia, the professor's competitor was the guy in the office next door. It wasn't another university.

Peter Winton:He had to raise more money. He had to have more PhD students. He had to publish more papers. Yada yada yada. Right?

Peter Winton:He was worried about the guy sitting in the office next door. He wasn't worried about Oxford or Cambridge or Manchester or Lees or Sheffield or anywhere else, you know, because what he was selling was teaching, but he wasn't selling it. He was trying to attract students to come and take it. Yeah? So, you know, the competition was completely different, but from his career advancement, from the advancement of his institution, if they all competed with each other, the whole institution was raised up.

Peter Winton:You know, everything got better. Once I got that in my head, then it was easy.

Ilya Tabakh:Super important. Just to draw that out in The US context, it really sort of depends what career stage the academic is in. But in many cases, folks go to academia because they want to maintain some academic freedom, right? And then if they're early, obviously, publication until you get tenure. So in The US, there's the concept of a tenured professor.

Ilya Tabakh:And then there's sort of maybe you are competing against the other top institutions because there's a limited amount of funding. And then also, it's an individual sport. Even in team performance, first author still means something. But that's the It's interesting because I sort of spent a long time training to be a professor and then escaped the other way. And so really, the understanding of incentives for sort of the diverse team that you were encouraging to build is really important if you're sort of doing this contact between academic and non academic.

Ilya Tabakh:So it's interesting that incentives is the place that you called out because I completely agree and have to explain to people all the time that people are in academia or choose to be at least partially in academia for different reasons than they would be in industry, Right? And that's surprising for a lot of people, but I think it's a really important point to sort of call out. I just wanted to I love that that's what you came up with, I'm, you know, a huge plus one for me.

Peter Winton:Yeah. And, I mean, shamelessly, I leverage that. You know, if I get more money for more PhDs, if I could get more kudos because we'd identified a novel piece of IP that Rolls Royce could patent and use, any of those things, you know, he helped me and that was my way of helping him. But I had to realize that helping him meant helping him

Peter Winton:do better than the guy in the office next door.

Ilya Tabakh:Yep. Everybody's got to win. How you get stable cooperation is when everybody benefits.

Peter Winton:Yeah. And the company benefited. There's absolutely no question. They came up with some fantastic things and they still are. You know, even today they are still coming up with stuff that you just wouldn't believe, You know?

Peter Winton:Like, little little snake arms, right, which you can send in through a borescope hole in an engine. Right? And it will follow. It will tip follow and go around the engine to the place you wanna have a look at. Alright?

Peter Winton:And can you imagine that it's like a cat's tail, right, but it's like a meter and a half long. It goes through a nine millimeter borescope hole. Nine mill it's not even half an inch.

Terrance Orr:That's incredible.

Peter Winton:It is. You're absolutely right, Terence. It is incredible. But the whole basic science of that they came up with. And without I mean, no one else in the world came up with it.

Peter Winton:They came up with it. You know? So that's, mean, that's the sort of thing that just amazes me. But if they're gonna put that level of hard work in, then boy, I need to put some hard work in to help them out.

Terrance Orr:Peter, you mentioned earlier that, you know, you were trying to figure out like, what is the role really and how do you actually do it? And what was it at this point did at this point, did you have exposure to the role of an entrepreneur in residence or had you ever heard of this role yet at this point?

Peter Winton:At this point, I had never heard of the role. I'd never seen I mean, I knew what an entrepreneur was and the university had a pretty good track record of exploiting their technology. I mean, major thing was the CAT scanner. So the CAT scanner was invented at Nottingham. The technology was invented at Nottingham.

Peter Winton:It was licensed to others and they made a huge amount of money out of it over twenty years of the patent. So they had a great track record but it never really impinged on me and the reason for that is because as an industrial sponsor, our contract was that the intellectual property that was generated out of the PhD research or the specific research projects if there was one using the researchers in the UTC, The intellectual property that was generated belonged to Rolls Royce, not to the university. So if you like, Terence, I could see this stuff being generated, it was going into Rolls Royce and we were exploiting it. But I've never heard the term at that point and obviously there was no opportunity for the University of Nottingham to use any of that in spin outs. So in other words, because of the arrangements of the contract, I never got to see that side of what was going on.

Peter Winton:So no, I'd never heard of the term.

Terrance Orr:That's incredible. Now I'm gonna ask you the money question, which is, know, after all of that exposure of working with the UTCs, right, you've had a very storied career, right, this very weird three letter job title, you know, opportunity role pops up called the entrepreneur in residence. How did you hear about it? Had you ever heard about it at that point in your journey? And walk us through how you landed your first EIR role.

Peter Winton:So had I ever heard about it? No. I think I've said no. I'd never heard about it and didn't really know what it was. About, I don't know, six months, but I decided the year that I retired, I decided at the beginning of the year I was going to retire at the end of the year.

Peter Winton:And over a period of months, when everything was worked out and I started to tell people. And about, I don't know, it must have been about three or four months before my retirement date, my very good friend Kate Barnard, who was also involved in the running of the UTCs came to me and said, I've got the very thing for you to do when you're retired. And I said, Oh yeah, what's that? And she said, You're going be an entrepreneur in residence. So I said, Oh yeah, what's that?

Peter Winton:She said, I don't know, but you're going to be one. So, okay, fine. So obviously we do a bit of homework at this point and we start to find out. And it was by applying for a grant to the Royal Society, which is one of the original scientific societies, one of the first in the world founded by such people as Isaac Newton and others. And so I thought, okay, fair enough.

Peter Winton:Read through the grant application what you needed and I needed the support of somebody at the university. So I went to see the dean of engineering and I said to Sam, you know, this is available. I'd like to give it a go, but there's no point in giving it a go if you're going to look at it and say, not interested. So we went through it together and he said, you know what, I am really interested, and this is what I'd like you to do. So I wrote that up as a project.

Peter Winton:He wrote a letter of support and I submitted it and thought, well, here you go. Kate, I did what you asked me to do. I had no expectation that anything would happen. About a month after I retired, I got a letter from them saying, you're accepted. We'll pay you, and you can go and work for one day a week in the university.

Terrance Orr:So effectively, Peter, you did a favor for a friend, you know, for applying for the EIR role, a role that you had never heard of before in all of your years of working and took the leap, right, to just take a look at it. And, and I think that's a testament to who you are, right, and from what you've told us so far on the podcast, because I think it's important that most people have never heard of the role, so you're not alone there, right? Number two, most of the time the EIR role will find you. You don't find it, you know? And in this case, your friend found you to be a good fit for this mysterious role.

Terrance Orr:Yeah. And you just happened to say, this is a good enough person. I'll take a look at it. Right? So And when and when

Peter Winton:I read it, it it it really was, Terrance. I would say 50 no. That's too much. 20% of the job I was doing with the UTC, identifying the intellectual property, trying to decide whether it was worth protecting or not. I mean, the option was if we didn't want to protect it, we could give it back to the university and talking it through.

Peter Winton:And one of my other roles in ManTech was I was the liaison between manufacturing the manufacturing function as a whole, not just ManTech, and our Patent's Office at Rolls Royce. So our guys would come up with clever ideas and they would put in business review forms and they would come back and say this has got this novelty, da da da, And I was the one who liaised with them and said okay fine, well you know we should pursue this one because you know this area would be helpful if we could get a lead over the competition or you know we could license this out to one of our suppliers and improve the cost or quality of our products or blah blah blah. So I had that sort of experience. Never I've never crossed my somebody said, what are you doing here? I just say my job.

Peter Winton:Never crossed my

Ilya Tabakh:By the way, just jumping in real quickly. I think for physical products, being able and being sort of at the heart of the patent novelty footprint is like a crazy interesting role. I spent a little bit of time. I think I spent like three months at the IP group within Cisco Systems, so the networking company. And so they had done a bunch of M and A work, but they also had like 10,000 patents on, you know, from like network telephony to whatever.

Ilya Tabakh:And it's just interesting because they're sort of folks that invented, you know, things that we rely on on the Internet every day, you know, and were very good at You know, Cisco also got sued for lots of money every week or month as companies would sell, transact, patent portfolios would go. And so the other thing that was really interesting to me was the, in those lawsuits, the quick ability to say, No, this was in the market three years before this thing was issued. Let's not waste any legal money. Or, Hey, we're actually going have to fight this. This is important.

Ilya Tabakh:But it's just like, unless you've been in that role, that's like a really weird Because there's a little bit of the, What's the commercial potential? Where does it sit from the protective standpoint of the portfolio? And the reason I say physical things is in software, patent and copyright are, at least in the Western setting, on a whole different level than in hardware. Because if you have a hardware kind of patentable device, you can keep people out of the market. It's pretty effective.

Ilya Tabakh:And so I just wanted to sort of call that out. That's a pretty unique experience. Even in your body of unique experiences, that's the one I sort of stumbled onto because I was very curious on how intellectual property allowed technology companies to sort of enter the market. But, you know, I got a whole life's worth of lessons in a very short period of time. So I just wanted to sort of identify kind of the unique nature of that, especially for a technical person.

Peter Winton:Yeah, is unique and it's one of those areas where people just in most people's head, the answer is a patent. What's the question? That's not always the way. The recipe for Coca Cola isn't patented.

Ilya Tabakh:Trade secret.

Peter Winton:It's a trade secret. The trade secret is indefinite. And the other thing interesting that you say earlier about patent versus copyright or both in software. And we did a lot of work in Rolls Royce very successfully of patenting processes which involved the software. That was something I actually introduced into the UTC was, Guys, you've written this little subroutine to go with your ANSYS FEA work.

Peter Winton:It's very clever. It allows us to do this. So you go identify that to somebody because I'm not sure that Rolls Royce own it. It's just a side issue. It's not an output of what we've commissioned, but it's got value.

Peter Winton:And the university now has a really good arrangement with a company and a lot of these little, what would you call them, they're not algorithms, they're a bit beyond algorithms but these add ons that go on to things like FEA analysis or CFD or stress or whatever, they are actually bundling up as an add on software and this company are licensing to sell it. So, you know, there is a lot of stuff like that. But I'll be honest, from a personal perspective, I stay well clear of I've got an app for this or an app for that. Because it's not a market I understand at all. You'll have guessed by now that I don't even dabble in life sciences anyway.

Peter Winton:Don't understand that either. So in that respect, you know, because of the IP side of it and because I understood it earlier, I've always stuck to the mechanical engineering bit that I've been working around all my life.

Terrance Orr:I love hearing you guys talk about IP as somebody who has some legal training from a law school and understanding that you guys actually know the difference between different types of IP, which is great to hear. And and so, you know, I I can geek out on this topic of design patents and copyrights, trademark, all sorts of forms of of IP that you can really get into frankly. And and and I think that's a value lever, right, that that a lot of companies leverage when you're building hardware or physical things, Ilya, as you would call them versus you're trying to do something in software. Right? Like, I would feel this a lot when when I used to build data storage systems at, IT infrastructure company called EMC Corporation at at the time, you know, that was acquired later by Dell for a lot of money, that that you can go check it out.

Terrance Orr:I think it was 65,000,000,000 plus, and still the largest I think second largest acquisition in technology history and I learned a ton around like the IP of like physical things, right, during during that time. But I had no clue the value of that because at the time I hadn't gone to law school yet. Right? So you guys got a chance to learn it in the trenches. Right?

Terrance Orr:At the time, I learned it in the trenches building data storage systems and then went to law school. So I think the fact that you got a chance to cut your teeth doing that in real time, Peter, no legal training, right, just the technical knowledge and know how and applying that, I think is incredible.

Peter Winton:Yeah. And I think, again, I agree with you, but I think I regarded having a fundamental understanding of the legal situation around different types of IP protection as something I had to do because I had to understand it otherwise I couldn't properly support the UTC, You know, so have to say the Royal Society decided they wanted me. So I I totalled back into the university and said to Sam Wright, well, what are we going to do? And he said, well, let's start by doing this. And I spent two wonderful years going around getting to know people, picking up on a couple of good ideas and was asked at one point to support a group going through a process we call iCure Explore, think it is.

Peter Winton:Just used to call it iCure. But it's is it? Industrialisation and Commercialisation of University Research And it's run by Innovate UK, which is a government funding organisation. And it gives an entrepreneurial lead three months to actually go round the world and find out if there's a market for their idea. And then at the end of it, they come back and say, this is what I found and this is what I want to do with it.

Peter Winton:So they can say, yeah, I found it, but I need to do more research. I found it and I'm going to license it. I found it, I'd like to have a startup. And there's another couple I don't I mean, the other one is, well, I didn't find it. It's around the world and nobody's interested.

Peter Winton:But, okay, you know, 40% of all startup failures cite no market need' as one of the reasons they folded. Know? So it's a wonderful way and University of Nottingham have now got, I think it's 38 spin out companies on the go And since 2005, I think it is when they started, they've only had three failures and they go through this IQR thing. So this was how it all started. I think my the thing I found most interesting was, I would say 90% or more than 90% of all the academics I spoke to, their priority was an academic career.

Peter Winton:They wanted someone to use their work, but this wasn't about founding a spinout. It was about finding ways for their research to be used and give benefit and impact outside the university. And that was the most interesting thing and that makes the whole entrepreneur in residence thing very different because now you're not worried about whether it's going to get exploited or not. What you're worried about is how can you get the resources into that academic that allow them to convince somebody that they should be using it. You know, how do you assure that if it's I mean one of the things that I think what's it called?

Peter Winton:I think it's Terra Nova, is spin out company. And they monitor movement in the earth, you know, huge movements in the earth for all sorts of things. But ensuring that the university maintains the capability to keep all that up to date is important. You almost have to go and find the support mechanism before you find the customer, if you see what I mean. If the academic is saying, Oh yeah, yeah, if there's a professorship at Imperial, I'm off.

Peter Winton:Well, that's no good to the university he can't maintain the IP that he's developed. So I think it's quite different to a lot of other ways of doing it.

Ilya Tabakh:I do want to say, though, I think that once you know what problem you're solving, back to this incentive for the academic, I think it's a lot easier to get there. And so I want to sort of commend you on figuring that you probably ended up solving a problem that you didn't initially come in for. That's sort of a testament to looking at and saying, What have we got going on here? What are we trying to do? In our discussions, I think you mentioned that you've done like six spinouts ish in your time so far.

Ilya Tabakh:Yeah. And so I'm sure there's stories of great success, maybe less success. Can you talk about kind of maybe the first successful one and kind of that portfolio and maybe what was surprising and not surprising about those experiences?

Peter Winton:So the first one I did was it's actually quite a nice little story. You don't often get to see the things you do come to fruition. I'll try and not drone on about this. One of the difficulties that you have when you're servicing products that undergo corrosive or high temperature atmospheres is that the fastenings that hold them together corrode and getting them apart becomes a mechanical problem. So you've, you know, just take a simple nut and bolt, if you're going to get those apart, you've either got to cut the bolt off or split the nut.

Peter Winton:And that's fine except that if it doesn't go quite right, you can cause a lot of damage to the parts that are being held together and those parts can be very expensive. You've also got to consider that if you're trying to take a wind turbine apart, having a large bolt splitter with a lot of mechanical forces in it, 150 meters in the air isn't something that people readily volunteer to do. Okay, so we have the same problem with a gas turbine. Parts get corroded together and if you can't take them apart, the two bits they're holding together can often be very expensive to replace and time consuming. So I commissioned a piece of work to use electro discharge machining or spark eroding as people might know it, to take apart nuts and bolts.

Peter Winton:And that was fine and we did the work and it got some traction but not a lot. So the university decided that they would have a look at this, see what patents were around because a lot were held by another company and not by Rolls Royce and whether they could do anything. And what they decided, it was before I got involved, was that yes, they could and they could do it actually quite successfully. So I was roped in because the guys at the university knew what my background and my history was with this. And I took this guy through the iCure, so two months before prepping it up and applying.

Peter Winton:Three months talking to him every week, helping him, keeping him enthusiastic. And it was in the middle of COVID so I had do it all from his bedroom, was, you know, a slight challenge. And we came to the conclusion that yes, there was a market out there. We had several people interested. So I helped the university put the company together to sort out where the IP was and where it wasn't and what I thought we needed from Rolls Royce or didn't need from Rolls Royce and how we might get it.

Peter Winton:They started the company. They secured a grant for a year to start the company and they started developing the product. And what are we now? We're now three years in. They have sold a couple of machines.

Peter Winton:They've got a couple of people interested in machines. They're in their own unit in Nottingham and they are now starting to develop in different ways. Initially, we were just gonna sell portable machines so people could take the machine to the product, extract whatever it was, and separate the assembly. But we discovered that people actually want fixed machines. So they've got a fixed thing they want to do, plenty of turnover on one type of product and they just want to take, in this case, nuts and bolts off it.

Peter Winton:So you wouldn't say it was accelerating away, but it is certainly moving very well at the moment. It's just another injection from an investor and it's been really great fun just watching it grow. And I go in probably once every two or three months and see them, or one of them gets hold of me and says, Can you come and talk about this? And it's been great fun to watch. I think my learning point from it was that these things never move quickly.

Peter Winton:Don't you know, this is not Rolls Royce. You have not got to get this to a certification day. It'll do what it does at the speed that it does it. But, you know, what I try to do is coach them, help them, support them, and, you know, wave a flag to the technology transfer office. I think there's something that we need to do.

Terrance Orr:And to that point, Peter, you you mentioned during our prep that you strongly believe that two years is too short Yeah. For an entrepreneur in residence role.

Peter Winton:That's right.

Terrance Orr:And nothing less than three years. Tell us more about that.

Peter Winton:So when I got to the end of the, well, no, before the end of the two years, the guy who runs the scheme at the Royal Society sent everybody an email saying, right, we're opening up for a third year. So if you'd like to do a third year, please apply. So again, I went back to saying, blah, blah, blah. But when I came to summarise for that, what I'd achieved in the first two years, it seemed to me to be not a lot, really just not a lot. I mean, had some impact on the things we were trying to effect.

Peter Winton:We certainly got a lot of academics interested in the fact that they could exploit their IP and they could personally benefit from that as well as it being a promotional enhancement. But I just thought I've not really done much, you know, apart from Sam and the Syntam thing, you know, that I've just described. And so I did the third year and at the end of the third year I thought, actually I've done quite a bit more, but not in that year. I finished off things that I started right back at the beginning in some cases. So at the end of the third year the university said please stay on our dime and so I have and there are now a lot more things that are reaching a conclusion and with the speed that university works there's a lot more things they've now managed to understand and academics come and knock on my door now and things like that.

Peter Winton:So I'm not sure what you can achieve in two years. Mean one thing I know is if you go in there and say right I'm going to establish these workshops and I'm going to get an entrepreneurial spirit into the university and you know get the students interested forget it. Forget it. That's not what you're going to you're never going to achieve that and even if you get it rolling when you've left it'll just stop rolling. That doesn't work.

Terrance Orr:What do you think those blockers are, Peter, inside the university as well?

Peter Winton:I don't think there are any Well, okay. I don't think the university and I don't just mean Nottingham because obviously there are quite a few, I think there's about 40 of us EIRs now in the Royal Society Industrial Fellowship. And I don't think any of us would say that the universe it's not a blocker. I think the problem is that the people are not very good at picking ideas and focusing on them. Okay.

Peter Winton:Today, the world is full of process. Everything has a process. Nobody trusts anybody. Right? So you don't trust your doctor, your policeman, your lawyers, your dentist.

Peter Winton:You don't trust anyone. Right? You go to the dentist, the dentist says you need a filling. Right? You go home, on the Internet.

Peter Winton:No. No. I don't. And you go back and you say, no, I don't. I've looked it up.

Peter Winton:I don't need one. And so everybody has a process and all objectives that people have in their careers are set by the process, if you see what I mean. To turn this handle until you achieve this result. So I don't think that the universities actually understand that what we should be doing now is looking at the ideas that come up and picking them. And I think one of the reasons they don't do it is the fear of failure.

Peter Winton:So they pick an idea, run with it, they put money and resource into it and it doesn't work. To which my answer is, well, how do you think it works when people get startups going? 95% of them fail. So what makes you think that you can have a better track record of that? And what makes you afraid of actually matching the existing track record of the world?

Peter Winton:So I think that's one thing. I think the other thing is they don't move with speed. There are points at which, oh yes, Yeah, this is a really good idea. We should do a proof of concept. You should apply for this funding.

Peter Winton:Okay, fine. I'll write the thing out today. No, no, no. It doesn't open for three months. Excuse me?

Peter Winton:You know?

Terrance Orr:You're ready to go today. You're ready to do it right now.

Peter Winton:Person who's got the idea, Terrance, is ready to go today. They're enthusiastic. They want to get it done. You found them a source of funding. They'll write the grant application tomorrow.

Peter Winton:And it doesn't open for three months. How do you think they're feeling in three months time? So I I I don't think the university my experience has been that universities don't block anything. It's the way that they think that blocks things. Well, no.

Peter Winton:It doesn't. It's the way that they think that doesn't get things going at the speed that you would hope. It doesn't capitalize on people's enthusiasm, etcetera, etcetera.

Ilya Tabakh:But but just to draw out this without being too long winded, but it's a pretty important topic, I think. I think most people read about how this happens in the world, right? And so there's sort of this folklore around how you start ideas and build things and everybody's young and in a garage and, right? And what you're saying is actually not just unique to universities. In most corporates, nobody has had the or very few people has had the experience of starting a new business line, right, or commercializing a new concept and having it become a material part of contributing to the P and L, right?

Ilya Tabakh:And so in many cases, the things that they imagine that it's going to take to do these things are not the things that it's actually going to take to do these things. And so a lot of the skill set and perspective that's necessary, I think that's part of the reason why I really like this idea of entrepreneur in residence. In order to be an entrepreneur in residence, you actually have to have the, as Terence was saying earlier, in the trenches experience of capturing and creating value. And then you can take that and translate it into the residence. But just to pull that apart, a lot of the established institutions, whether it's corporates or universities or others, this is just not a skill set that's, you know, kind of trained for and reinforced.

Ilya Tabakh:Most folks do what we're talking about despite the structure, not because of it.

Peter Winton:Yeah. And

Ilya Tabakh:so just to point that out.

Peter Winton:That's that's right. And I think the other thing is that all institutions, whether industrial or academic these days, in my experience, have all sorts of hoops you've gotta jump through. And it's long past the time where some of the people who create these hoops need to sit back in their chairs and say, when I ask them to come and present to me, what value am I adding? Because if the university is going to commit a 6 figure sum to one of its startups, I understand that the vice chancellor really ought to know about that. Right?

Peter Winton:But the vice chancellor does not need a twenty five minute presentation and a ten minute q and a. K? If the vice chancellor doesn't trust the person who has put this together and goes to the vice chancellor and says, I think we ought to do this one. What the hell are they doing? You know?

Peter Winton:If you you know, why have a dog and bark yourself? If you see what I mean. And I just think that a lot of these review boards and things like this in all walks of life, I don't blame Nottingham or any university or any business, they really ought to ask themselves the question, what value am I adding by having this? You know? Well,

Ilya Tabakh:you know, just to kind of move forward a little bit, you're six years in now. You know, you've done quite a bit and you're accelerating the pace. What's actually keeping you engaged and excited about, kind of your EIR role at this stage? Can you talk about that a little bit?

Peter Winton:Yeah. I think what keeps me engaged is being surrounded by some incredibly clever people. I just love it. You know, it's, I don't know whether I'm living my youth vicariously through them because I never did it. I never did a degree and, you know, exams.

Peter Winton:I don't have letters after my name and things like that. But they are such clever people. When you explain to them, mean we spoke earlier about being a translator, know, in fact, I don't know if I've got it. If I've got it, I'm gonna read this to you. You can cut this out you don't want it.

Peter Winton:Where did I put this? Just a minute. Because this I think for me, this typifies what goes on. Here we go. So this is, something I got involved in through reviewing an application for a grant for some money to do a proof of concept.

Peter Winton:They were asked to summarise the work and this is what it said. It said, the biological world is curved from the subcellular to the continental length scale. Cells sense the complex shapes of their surroundings and respond to these stimuli through the transduction of physical stimuli into biochemical responses. In vitro, designed cell scale 2.5 d complex curvatures have been shown to drive cell migration responses. However, synthetic polymer biomaterials with stoichiastic microporosity, I.

Peter Winton:E. Those fabricated by emulsion templating or particle leaching, often showed limited cell infiltration into the bulk of the material without surface chemistry modification. Little has been done to translate the physical influence of defined cell scale curvatures into biomaterial design as a strategy to improve cellularisation rate of three d scaffolds, partly due to manufacturing technologies previously being too slow to make this a realistic proposition. So why don't you tell me what that's about?

Ilya Tabakh:Yeah. Only because I spent a long time in academia, really hard to make surfaces that help cells move because they transfer into the cells and they're hard to manufacture. And so if you can make materials that change the physical properties, then they'll change the way that tissues grow. And there's a lot of knowledge gaps in that area, they're interested in exploring that problem.

Peter Winton:So this is how I got it translated in order to attract somebody to think that this was a good idea. Okay? There is a significant clinical need to develop new bone graft treatments. Bone is the second most transplanted tissue after blood, but the current best bone graft options are either bone taken from somewhere else in the patient's skeleton, which creates a painful second injury site, or the use of powerful biological molecules that can cause unwanted side effects such as misplaced bone formation or even cancer. Our recent work addresses this problem by demonstrating we can control the response of bone cells using the shape of their environment by three d printing implantable materials with cell sized features.

Peter Winton:This reduces the need for biological molecules and minimizes risk to patients as the implant cannot escape the injury site. Or to put it another way, if you were to have an implant to replace a tooth, would you want a material in there that might risk another piece of bone growing into your mouth or breaking off and causing cancer? Or would you want one that would very rapidly grow the bone around the implant?

Terrance Orr:Literally, and gentlemen, that's how you translate as an eagle.

Ilya Tabakh:Exactly. That was the words that were coming out of my mouth. It's a masterclass of both translation but also one was a problem statement and the other one was a technology science statement. Right? And those different audiences, different perspectives.

Ilya Tabakh:Because you didn't in your second statement, other than three d printing and foreboding things, you didn't really talk about any of the things they described in their statement at all.

Peter Winton:And that's I'm not trying to demonstrate here what a clever club I am. What I'm saying is one of the reasons that academics find it difficult to get things out there, to get impact, to get benefits out of and see their research and use is that they they talk science, and business talks benefits. You know? And people that invest wanna know you've you've got to get straight through to their animal instincts, haven't you? I mean, it was another one I came across, which was a very clever lady who had come up with a method of getting the cells in our bodies to open up and allow things in and then close-up again.

Peter Winton:And she went through the scientific explanation of this and was in one of these iCure things and somebody said, you know, okay, so tell me what do people think? And I'm the business advisor, I'm not really supposed to say anything, this is for the, you know, the entrepreneurial leads. Total silence. So in the end I put my hand up and said, look, can I say something? And they said, yeah, go on.

Peter Winton:I said, okay, here's my 30 elevator speech. When you get older, your eyes will deteriorate. And one of the things that can happen to you is you get macular degeneration. And the treatment for that is to stick a needle in your eye. My idea is to do it with eye drops.

Peter Winton:You know, have I got to you yet? That's it. That's it. You know. So I

Ilya Tabakh:The only thing I would add to that is in science, right, your job as an academic is to contribute to the body of science. So it is enough, if you're established and well funded and whatnot to make the contribution, not to commercialize it. But that's back to your original point about, you know, what are the incentives and how do people succeed. I think that was the biggest disconnect that I saw is that, you know, on the academic side, folks were doing their job and contributing to the body of knowledge. But what's interesting is from the commercialization side, some of them still loved the idea enough, and they had worked out the science to where there was no more science to do, but they wanted to see this thing take root in the world.

Ilya Tabakh:And they were woefully ill equipped to engage in that conversation because they're like, Well, who do I write a grant to to build this thing? Right? And that's not how that works a lot of the time. So, it's really important to connect the dots there.

Peter Winton:And I think it comes back to what I was saying earlier about having good ideas and chasing good ideas. Because I don't know how it works in The US, but in The UK, every seven years the government funding body, UK Research and Innovation, hold a thing called the Research Excellence Framework and basically you have to put in your case studies and show how the money that they've put into your research has been used and had impact outside and they rate them. The higher the rating that you get impacts what money you get in the future. So there now actually is, Ilya, an incentive for our academics to get work out there and have impact. And it doesn't have to be monetary impact.

Peter Winton:It can be societal impact. It can be anything. But it has to have an impact. And some of the ones that I unfortunately can't talk about them, but some of the ones that I was reviewing last week are absolutely incredible. How really simple things have had a huge impact on the environment, on business, on industry, you know, it's quite really, really interesting.

Peter Winton:But these are now things that are helping to maintain the survival of some universities, particularly research universities. And these are things that are now being taken into account in promotions and things like this. Very slowly an incentive is being created. But like all these things, people that have not grown up with this in the system have got to move out of the system before everybody who's coming up is used to it. It's important that you don't ever lose sight of the fact that having societal impact of some form or another is going to create a far better environment for universities than it does at the moment.

Ilya Tabakh:The balance has always been that some things that have big societal impact aren't known when they're first being explored. In The US, it's a little bit broader. So generally, the National Science Foundation and others have looked at what is the impact of your work, especially for applied research. For basic research, that's a little bit of a harder question. And so there are folks that have both created basic research institutions and still some federal research that does that.

Ilya Tabakh:And it's always kind of a balancing act because if you look at all the examples, but some of the well known ones are Dijkstra's algorithm for routing on the internet, Right? A traveling salesman problem was just a mathematical curiosity. Before, it was a thing that ran the backbone of the routers of the internet. And so it's always kind of but, yeah, to your point, it's gonna take time even if there is sort of some forcing functions for that ecosystem for sure.

Peter Winton:Yeah. And and we have to be awake because the world may change in the time we're waiting for this to happen. And then it's no longer of its time, You know, so, yeah, we have to be awake to these things. It's a joy to be there, you know, going back to your original question, Terry. It's a joy to be there.

Peter Winton:I love being there because these people are so clever and because they do such good things and because going back that's where I wandered off to my example and because when you show them things like that, they can immediately get it. They immediately get it and they will go off and write things like the second one when they do it. That's incredible. You know, talk

Terrance Orr:to for another hour about this about this whole topic, Peter. And it's so many so many, like, we might have to find a way to to to get you back on so we can do a part two about it. But in the interest of respecting your time, you know, I wanna make sure that we get you out here as we promise. But for those that are interested in learning more about your work or the companies that you've helped spin out, you know, where could they find you in your work and how can they get in touch with you?

Peter Winton:Well, they can get in touch with you through LinkedIn. That's the one I use most. I'm a bit of an interrupter on LinkedIn, I write about what I do on a regular basis. The next best way is to look at a website, I can't remember the address, but Nottingham Technology Ventures. Okay.

Peter Winton:That's the arm's length wholly owned company that the university uses to umbrella its spinouts. So if you go and look on there, there's a little bit about each of the spinouts that the university have done. You won't find my name or the name of anyone else in the technology transfer office on there, but this is the work that they do. So those are the two main places that you can find out. But yeah, I mean, if people are interested, it's fine.

Peter Winton:I mean, just drop me a line through LinkedIn and I'm sure we can talk about something even if it's not what they want to talk about.

Ilya Tabakh:Amazing. And so we'll put those kind of links in the comments, and we'll add some extra resources to folks for the episode. So that'll be great. And then I guess just to take us out, what what advice would you have for, you know, kind of an aspiring EIR in a similar role to yours now that we've gotten a chance to kind of dive in and learn about pieces of your story?

Peter Winton:What advice would I have? I think my first piece of advice is you have to be good at identifying good ideas. By which I mean, when you see an idea, you must be able to connect it to something you know would be better if the idea was out there. You know? And it doesn't really matter what it is.

Peter Winton:My second piece of advice is stick to what your experience is. I mean, I don't mind going and coaching someone in a life sciences spin out, but don't ask me to help them with pivots or marketing or any of that sort of thing because I don't know enough about what they're doing to actually help with that. So, but from your point of view, you know, you need to be able to place the idea in a context that you know is going to work. I think the last thing is, which is in two parts, is the two things that I think I always work by. One is, is it of its time?

Peter Winton:And the corollary of that is what we talked about earlier, is letting go and quitting and realizing that, yeah, you've done six months on this, you haven't got anywhere. It's not of its time. Leave it alone because it might be of its time while you're still around and it might not. And the corollary of that one is being able to say I don't know and then going to find out. Just being honest with people.

Peter Winton:But, yeah, think for me, part of the real enjoyment of it is the fact that it's not about me anymore. I don't have any objectives. I don't have pay reviews. I don't have performance chat. None of the above.

Peter Winton:If people don't want me to help them, they don't ask me. It's very simple. If they do want help, do ask me. I've got too many now, but yeah, know a good idea when you see it, make sure you know where the good idea is going to go, be able to say I don't know or just drop it if it's not of its time. And I think lastly, know the rules of advice, which is don't give advice if you expect it to be taken because you'll only be disappointed.

Ilya Tabakh:I think that's amazing.

Terrance Orr:We're gonna wrap it up with the last one here, which is we always like to give back to the people who give their time to us coming on the podcast. So we'd love to know how can the entrepreneur network, the EIR Live Network help you and do what you do best right now at this current stage of your life?

Peter Winton:I would think the best help is really finding, is being able to throw something out there saying, does anybody know anything about Or does anybody know anybody who? Right? Because for me, part of the lifeblood of helping these people is knowing who to talk to and knowing people that can help. You know. So I think if there were an, you know, if you establish this big network, the best thing would be, I don't know, a WhatsApp group or whatever, but, you know, some sort of group where we could all go and say I've got this guy, he's got this idea but I need someone who works in the clothing industry to help me because I think there's an application, you know that sort of thing.

Peter Winton:I think that would be, I find that the most useful thing about, we've got, I need to say, there's a WhatsApp group for the Royal Society of AIR's, but I find that the most useful thing is people come on and say, does anybody know anything about this? You know, has anybody applied for that? You know, that is the most useful thing. It's really being able to answer. When you say I don't know, it's being able to find someone that can help you answer and know.

Peter Winton:So that's what if if you had a network, that's what I'd like to get out of it.

Ilya Tabakh:Amazing. I think we should leave it there. As is our tradition, we've gone somewhat over our initial time. But amazing discussion. I'm glad, Peter, that you had the opportunity and took the time to come on and really dig into parts of your kind of journey and career.

Ilya Tabakh:And I'm excited for kind of our audience and our network to take a listen. So I really appreciate the time. And, you know, as Terrance said, maybe there'll be an opportunity to dig in a little bit more because there's, you know, way more experience and insight than is time on one podcast. So I really appreciate it.

Peter Winton:No. I've enjoyed myself. So I'd be happy to come again, Terrance, if you invited me and Nelia. So, yeah, thank you very much for putting up with me.

Terrance Orr:This episode was, was one that could be sort of thought about with the deepest level of experience that you can think about. You know, when you talk about experience that could translate into other things later on when you're an entrepreneur in residence. Peter, you know, displayed that and much more, today. And it really left me thinking in sort of three buckets, Ilya, thinking about his experience because we know from the multiple EIRs we talked to and Peter was no different today was that no plan, no first plan survives contact. Right?

Terrance Orr:Like and sometimes the second or the third plan won't survive contact with the enemy or the organization or the residents, frankly, that you're going into. And Peter is able to draw from fifty plus years of experience that gives him hindsight that also enables the foresight and the insight that he has today, you know, and to do the work that he's doing as a at the Royal Society and the university. So that's really my impression of the episode today and how I would think about it and wrap it up because I don't wanna steal the thunder from the other things that our audience is gonna hear. What do you think?

Ilya Tabakh:Yeah. No. Absolutely. I mean, just to pick on on your perspective a little bit, I really enjoyed that he was able to sort of dive deep. And I mean, you even called it out in the episode where it's like, you know, that's how you know you really were in there and doing the thing because you can peel it back, be sort of in the trenches, so to speak.

Ilya Tabakh:And it was really enjoyable for me to kind of listen to Peter and then even like in some ways have him realize some things that he hadn't really thought about. And so that's what really kind of a lot of these great conversations lead to, I think. The other part for me that was interesting is that he kind of had an informal education and preparation in dynamic systems optimization and many of the things that I actually get excited about and know. But like he did it in a very deep, like hardware manufacturing realm. And it's unusual a little bit, but he was able to pull into intellectual property, of the business case side of things, the actual physical production, what physics does for a jet turbine, just like all these pieces that I think make him kind of both unique.

Ilya Tabakh:And I bet you in like a university setting, I bet you in his university people find him really compelling because he can talk about, you know, when we did this thirty seven years ago, right? Here's kind of how And it's crazy because some of these technologies are thirty, fifty year platforms. And so in some cases, a lot of those insights are still directly applicable, let alone sort of a good lesson. So anyway, I really like that it's like really diving in with somebody that's both excited and an expert. And I think Peter's all of those things.

Ilya Tabakh:And also, I really enjoyed that we had our kind of first Royal Society, EIR. I've talked to a handful. But that international perspective and the fact that we were able to exchange notes on the academic setting, the industrial setting, everybody does it a little bit differently. But there's definitely places and ways in which it rhymes. And so kind of the final thought is I thought that was a good input, I'm hoping to bring more of that into our discussions going forward.

Terrance Orr:A massive plus one. The people are going to be in for a treat to listen to a true translator today. And we're going to do some live translation of all of his deep experience on the episode. So can't wait for you guys to tune in. Love it.

Terrance Orr:Thanks for joining us on EIR Live. We hope today's episode offered you valuable insights into the entrepreneurial journey. Remember to subscribe so you don't miss out on future episodes and check out the description for more details. Do you have questions or suggestions? Please reach out to us.

Terrance Orr:Connect with us on social media. We really value your input. Catch us next time for more inspiring stories and strategies. Keep pushing boundaries and making your mark on the world. I'm Terrance Orr with my goals, Ilya Tabakh signing off.

Terrance Orr:Let's keep building.

Creators and Guests